User Research – Methods and Best Practices course by IxDF

Lietotāju izpētes kurss ar ieskatu metodēs un procesos, kas saistīti ar izpēti.

Kurss palīdzēja man nospraust robežas starp to, ko dara lietojamības pētnieks, un ko - dizaineris.

Research plan theory

- Purpose - the overall question I want to answer

- Method - the best way to answer the question

- Participants - who they are and how we will recruit them

- location (adn equipment)

- script(intro/interview guide/questions)

- what data will you collect and analyse

- consent: purpose, consent form or verbally, voluntary, NDA

- communication

- time plan (without a specific schedule)

pilot studies - test your setup and script

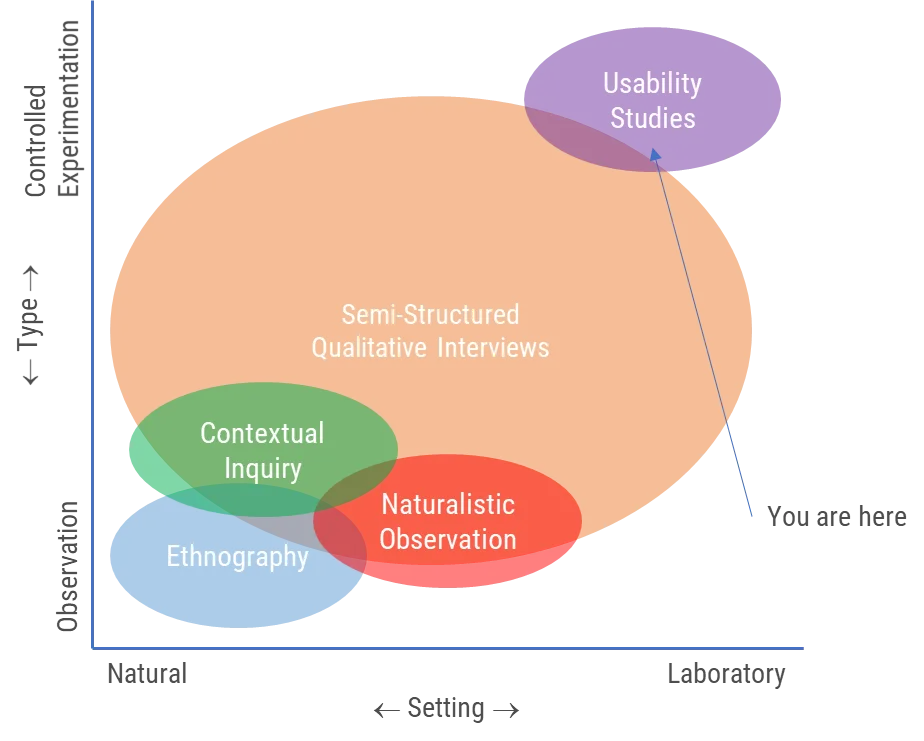

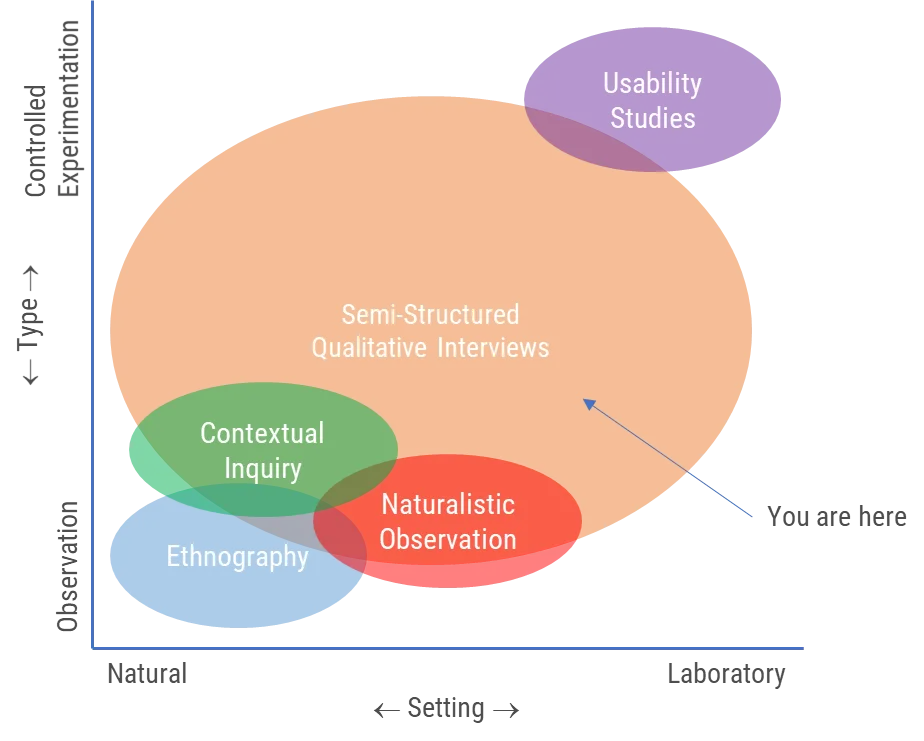

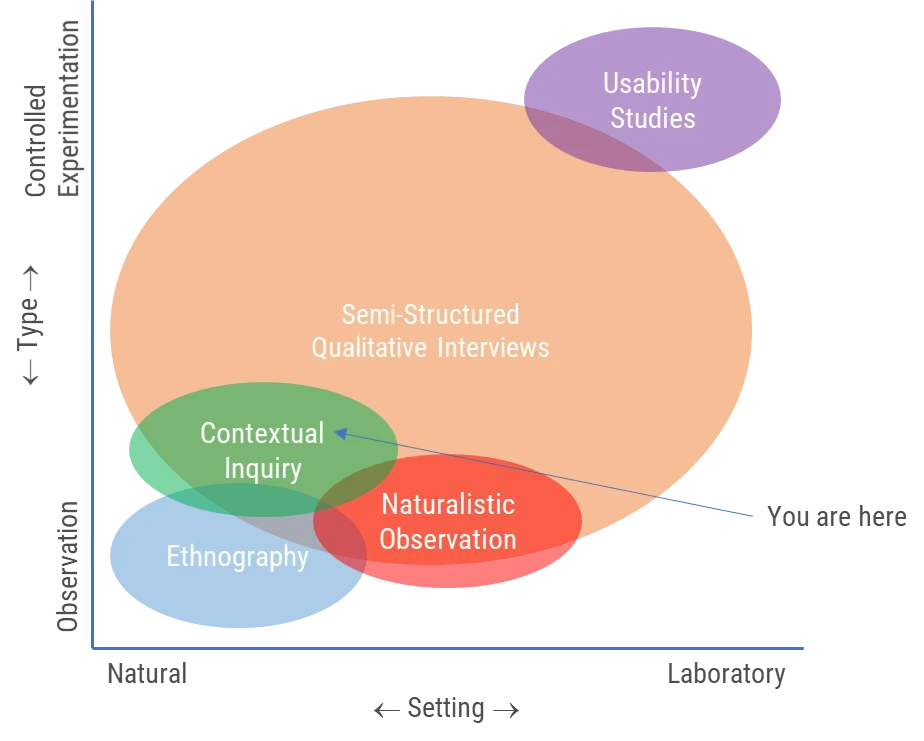

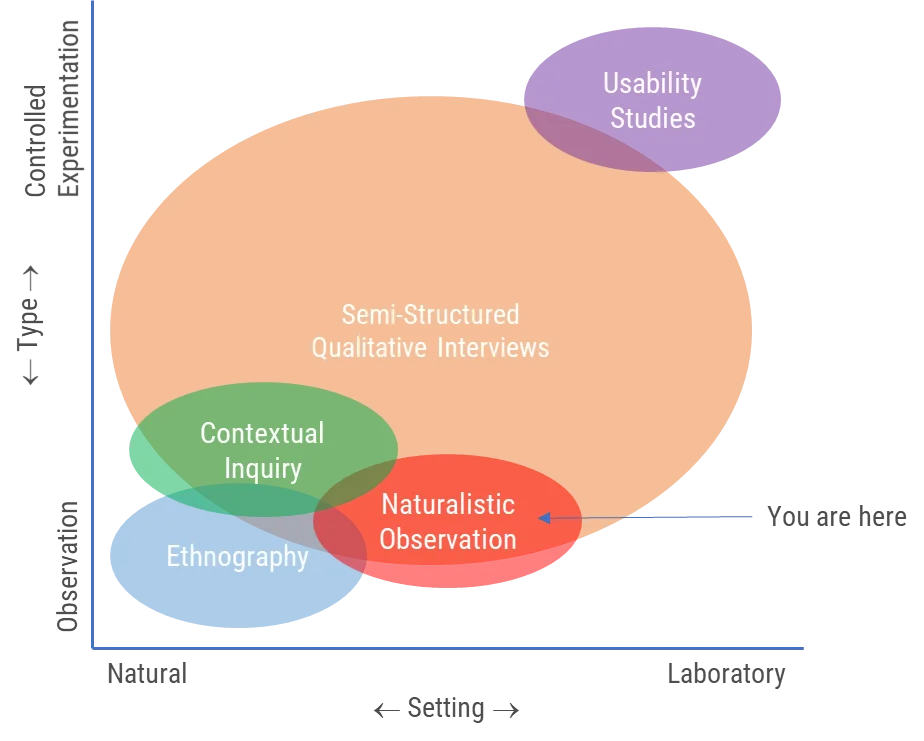

Usability studies

In a usability test, you can determine quite a few metrics:

quantitative:

- time on task

- success/failure rate

- effort (# of clicks/perception of progress)

qualitative:

- stress response

- subject satisfaction

- percieved effort or difficulty

what is measured

- success rate (100%/50%/0%)

- Errors per task

- of Confusions per task

Behaviour!

- task performance

- speed

- efficiency

- goal fulfilment

- expectation matching

Opinions (at the end of a test)

- how it looks

- thoughts

Data

- Visitors

- pages

- documents

Usability issues:

- not seeing something

- going the wrong direction

- thinking it’s correct when it isn’t

- missing a “rule” (typical design patterns)

you get out of it:

- confusions

- errors

- actual vs expected difficulty (gets out of the flow)

- highlights

- severity rating (impact vs % of users who had the issue)

- ease of use - do they get the task: failure rate 0%, partial success 50%, success 100%

planning usability test

Sample sizes

- surverys = ~240 - ~1000 +

- focus groups = 15-20

- usability testing = 10-15 users (5 users per segment)

- field studies = 15-40 participants

- card sorting = 15-30 (higher is better, as this is quantitative)

mobile = distracting

max 1 hour

10-15 tasks

psychographic perspective could be used instad of classic segments.

put easy tasks in the beginning, hard in the middle.

“I want you to think aloud - tell me what are you thinking and feeling.”

User test

testing expectations and make sure you tie it to business and user objectives

Pre-test (optional)

6-10 questions about anything that helps clarify who you are testing

The Test - listening mode

Go through tasks

monotonous tonality

ask reverse questions

use pauses and silence, use okay, uh-huh

let users struggle, he does it even up to 10-15min.

“Okay, you are helping us identify what we’re looking for.”

instructions at the beginning:

- Thank you for helping us

- Purpose of evaluation (here to get your feedback on design. No right or wrong answers).

- Use these tasks to find the answer on the site

- Think out lound so I can follow along (tell me what you are thinking and feeling). We’re video recording striclty for note taking purposes.

- Go on to the next task when ready (move at your own pace when you feel you found the answer)

- I will ask you some questions afterward when you are done. As we go through, if you have any questions, I might not be able to answer them.

Post test

interview style questions

subjective satisfaction

SUS - standard usability scale

“If there is 1 thing we could change - keep everything else the same and change 1 thing - what one thing would you have us change? “

“If there is 1 thing we could keep the same - change everything else and keep just 1 thing - what one thing would you have us keep the same? “

Dry runs - test the test

validate that tasks can be performed

verify that hardware and software are working properly

DON’T

- change tasks midway

- go in wihtout a back-up-plan

Test report

user advocacy attitude

“I saw this” is better than “I think this”

prioritize findings

keep it short (10-15 slides/pages)

show screenshots

include also positive things

prepare a summary

avoid harsh words and tones

try to report out immediately

avoid confrontations, be flexible with recommendations

User interviews

conversation with a set of topics to cover that flows naturally. It has a specific agenda, but is allowed to move away from that if the interviewee moves to another topic or says someting interesting to follow upon.

Good for generating insights in design projects as it is possible to explore the topics you have and have not yet thought about.

Pros and cons of semi-strucutred interviews

.. you should ask the concrete “how” and “what” questions before you ask the more abstract “why” questions.

- Good for the “why” people do things, their values and reasoning.

- Also good for sourcing ideas and making sure next research steps are on point.

- Bad with “what”. That is better done with observation as people don’t remember unremarkable things and take them for granted.

- Also, bad for getting an answer to questions like “would you like to use our product?” as people are bad at anticipating what they might do in the future or their attitudes to future products.

When to conduct user interviews

- for exploration: to form the knowledge basis before any design or research decisions are made, to gather context for moving forward.

- in combination with user testing: before and after usability tests, to get the “why” any actions or decisions were made.

- concept explorations: as you are in the proccess of making your concept, ask about the relevant problem space without revealing your specific soultion as that can taint the information gathered.

- in combination with observations: best ir afterwards, but while you both are at the context of performing the actions, ask to clarify and explain their thought. Or ask to explain their interaction as though explaining to a novice user.

Questions

prepare an interview guide and test it with a friend to check if:

- you are using understandable language for the interviewee

- the questions are ordered in a way that makes sense

The flow:

- easy, but specific questions at the beginning

- all the bulk of info you want to get in the middle

- reflective and reverse questions at the end

- how the information will be used (agency)

Tips:

- ask for specific instances (last time)

- invoke incidents particulary memorable (as these memories are more reliable)

- go with the flow! Ask questions in free-form, follow the thought of the interviewee

- building rapport is important to make everyone feel comfortable. allow for some off-topic talk if that does not take too long.

- best conversation flow is attained by asking follow up questions and listening carefully

Qualitative studies are mostly driven by questions, quantitative - by hypothesis.

Rapport equals trust plus comfort.

Follow-up questions

ideally—you should only ask one kick-off question and allow the rest of the interview to flow naturally from there. Obviously, you steer the conversation and you sometimes consult your interview guide, but if you listen to your participant, most of your questions can/will be phrased as follow-up questions to something the participant has said. In that case, you mainly use your interview guide as a reference to see if you have forgotten anything, to get back on track if you draw a blank and can’t remember where the conversation was going, or if the interview strays too far off-topic and you need help to get back on track.

- Introductory questions

Questions where your participants can make spontaneous, rich descriptions of a situation or context: e.g., “Can you describe the last time you…?”.

- Follow-up questions

Here, you follow up on something the participant has said either by asking about what the participant has just told you or simply by encouraging the participant to carry on with what he/she was saying by nodding, pausing, or saying “mm”.

- Probing questions

With probing questions, you ask participants directly to elaborate on what they were saying: e.g., “Can you give me an example of that…?” or “Can you explain in more detail…?”.

- Specifying questions

If you feel like you are getting too generalized a description, you can try asking specifying questions: e.g., “What concretely did you do?” or “How did that make you feel?”.

- Direct questions

With direct questions, you introduce topics directly, because you know they are either of interest to your project or based on something the participant has said earlier: e.g., “Do you have any experience with x-brand video streaming service?”. It is best to wait with direct questions until the last part of the interview, so that you give participants a chance to describe their perspective before you introduce your own interests.

- Indirect questions

If there are questions where you don’t want to ask the participants directly about their experiences with something, you can ask them more indirectly: e.g., “Do you think other people sometimes find the user interface difficult?”. The answer can reflect both the participants’ own experiences and how they interpret the experiences of others, so you should be careful how you interpret their answers to any indirect questions.

- Structuring questions

You use structuring questions when you want to change the topic of the conversation or to get back on track if the interview has gone too off-topic. In that case, you briefly acknowledge that you have understood what the participant is saying and then say—e.g.—“let’s move on to…”.

- Silence

When you conduct an interview, try not to fear pauses in the conversation. Leaving a bit of quiet time after your participants answer allows them to think and follow up with additional information. How quiet you can be is a balancing act, and you shouldn’t be so quiet that it makes participants uncomfortable. For example, some interviewees may pipe up with off-topic or tangential points, just for the sake of filling such gaps.

- Interpreting questions

You ask interpreting questions to ensure that you have understood a participant’s answer correctly or to prompt him/her to elaborate. An example of an interpreting question could be this: “Am I right in understanding that you feel that…?”

Data gathering

To choose the best method, first understand how much is the appopriate amount and kind of data you need for the question you are serving:

- how much data do you need?

- how you are going to analyze the data?

- what depth of data do you need to have access to?

Types of data, their pros and cons:

- photos: easy on privacy and to gather info about surroundings

- notes: easy to analyze; lower quality - write down only what you felt was important at the moment; useful to note surroundings and stuff you can’t get from audio recordings.

- audio recording: may make conversation lower quality and stiff

- video recording: often off-putting and intrusive, so may lower data quality; a lot more data to analyze

Thematic analysis

A thematic analysis strives to identify patterns of themes in the interview data.

Here’s an approximate process:

- Familiarization (transcript, first ideas for codes)

- Generating initial codes - brief descriptions of what is said (labels next to quotes according to what is being said and to the purpose of research)

- Searching for themes (grouping codes)

- Reviewing themes (checking if themes are coherent, contained and represent the data)

- Defining and naming themes (to tell a coherent and engaging story of data using themes: what and why it is interesting)

- Producing report (engaging summary of findings preferably with consented visuals, background info about the process and full analysis)

What is important is that the transcript retains the information you need, from the verbal account, and in a way which is ‘true’ to its original nature.

/ Braun and Clarke

Data within themes should cohere together meaningfully, while there should be clear and identifiable distinctions between themes.

/ Braun and Clarke

In naming themes, you “Define the essence that each theme is about.”

/ Braun and Clarke

For an interview, transcribe the audio and “code” its important points and insights until you have cohesive themes and concepts make sense. This is an iterative process and you might need to go through your data more than once.

- coding into themes will help you familiarize yourself with the data

- it is a starting point for a report to write along as you combine the info.

Grounded theory - theoretical saturation when more information does not provide more insight - you already know all there is to know about the topic and your assumptions are not contradictory both to each other and the data. This is the perfect time to stop a study.

Pitfalls

- confirmation bias: think you have spotted something early on the data that reinforces your existing assumptions => look for contradictory evidence!

- picking favourites when analyzing data

- overwhemling amount of data might make it hard to start, finish or narrow down. => dive in and do something, make it into manageable chunks.

- good analysis takes longer than data gathering, but for some people get bogged down by analysis

- get someone to talk to, to throw ideas around!

Contextual inquiry

Contextual Inquiries (CI) mix interviews with observations and are an excellent way to gain insight into peoples’ work processes, your users’ daily routines, how they use different products, and so on.

10-12 participants, session is about 2 hours long. Be prepared that 10-20% might not show up/be disappointing.

It’s an immersive process - dip into it as many of your colleagues as you can!

interpret the notes in first person to acknowledge it is about real people doing real things.

You - researcher - are the apprentice while you observe the master - participant.

Observation is by far the most important part of contextual inquiry. In fact, that is oftne the most important part of user research.

CI is helpful to make the organization aware of their users and how actually it works.

Four main principles:

- Context (in natural setting, researcher acts as an apprentice)

- Partnership (alternate between observing and discussion)

- Interpretation (make notes that are self sufficient for affinity diagram)

- Focus (casually discussing the topic, not steering away)

When to use?

when you need to know more about your users and their problem domain

- greenfield (new products): observe users working with current solutions

- brownfield (existing solutions, redesigns): decide what to observe:

- use of your existing solution

- use of competing solution

- whether to focus on problem areas or the complete process

Who is involved?

- driven by UX professionals

- market researchers and recruiters: who and what to observe, arranging visits

- development team members: observers in CI/empathy, interpretation and coding, affinity diagramming

- project stakeholders (product owner, sponsors): interpretation and coding, affinity diagramming

Alternatives

CI is a high level research - task-level detail is not the focus.

For task focus better options could be:

- paper prototyping early in design

- usability studies for existing solutions or later in design

CI is very qualitative and does not use many participants (often no more than 12)

For greater confidence of repeatability in results consider adding a “double check”:

- surveys

- analytics

- other quanitative methods

CI research questions tend to be big:

- What are the tasks and goals in this domain?

- How much variation in how users solve problems?

- What are the high and low points/good and bad experiences?

Practicalities

The setting of CI needs to be naturalistic. For complext problem domains you might need to make several sessions per participant, as the jounrey consists of many parts (for example, online shopping + item delivery + unboxing)

Time and effort

Time is about 10 person days for smaller study (6 interviews and 6 affinity diagramming participants) and up to 36 person days for bigger one (12 interiews, 12 affinity diagramming participants):

- Preparation takes about 1/2 - 2 days, depending on complexity

- Interviews usually take 1.5 - 2 hours per user

- Coding important notes would take 0.5 - 1 per interview

- and 1/2-1 hour preparing affinity notes

- Affinity diagramming would take 1 to 2 days per participant

Consent

try to get it in writing as otherwise you have to spell out everything they are consenting to on audio/video

participants can withdraw their consent at any time. If you feel they are doing it during the interview (don’t talk anymore, feel very uncomfortable) it is your professional duty to assume thei are withdrawing their consent.

Running a contextual inquiry

Introduction

- Thank participant for taking part

- Explain process (again) and emphasize there are no wrong answers

- Assure anonymity - you need to know what they actually do, not what they should

- Obtain consent and explain that they may withdraw consent at any time

- Outline the focus of your research

Session

- Observe and inquire, use a set of “starter” questions just like in semi-structured interviews

- Master-apprentice model

- Confirm notes where necessary

- Notetaking is important but must not interfere with observation and discussion

- small laptop with a quite keyboard

- or pen and paper (slower)

- You must be able to take notes effetively while observing or speaking (practice!)

- Notetaking is important but must not interfere with observation and discussion

- Stay in focus - don’t be afraid to redirect

- If you cannot observe some tasks directly, ask participant to walk you through them mentally

Notes should

- be self-explanatory (free-standing)

- focus on a single concept or observation

- identify the participants (anonymously)

- written in first person

- checked with participant if signigicantly reworded

I saw you did this, is this a good description of it?

I’ve written that down like this, is it like that?

T05-77 Kept ptices of hotel and car options in a paper notebook. It took several weeks to get the best price.

/Holtzblatt & Beyer

1 I use a minimal shopping list. Julie

/ course material

Recordings

Video:

- not ideal as people do not behave normally while being recorded. It can be intrusive and intimidating.

- Participants may withhold permission

- Difficult to maintain anonymity

- But clips can be extremely persuasive

Audio:

- generally more effective and less intrusive

- easier to maintain anonymity

Transcriptions

- possible, but quality and cost can vary dramatically

- machine transriptions are usually trained for a single speaker

Timestamps

- cool to use on Word to locate notes on a recording.

Photos

- take photos wherever possible

- participants “in action” anonymously - great images for personas

- use photos in sessions with others

- always asn for consent!

Artifacts

- things that get used or created in the process

- can be real (paper forms) or virtual

- take screenshots of all artifacts to refer to them

Close

- Thank participant for involvement and the value of their contribution

- Provide compensations when appropriate

Coding and interpretation

TODO futher reading on coding about Grounded theory and check out a detailed discussion on challenges of coding and also a coding pyramid

interpretation sessions help fit the research and its findings in the wider project.

Analyzing results

We are doing research, the design comes later.

“Modelling is only done when absolutely essential”

Affinity diagramming

around a thousand cards printed, in a workshop a group of people label and categorize them by key themes.

it is good for:

- familiarizing stakeholders with user research

- stimulating design ideas (problems, solutions, motivations)

colors as category labels:

- yellow/white = original note (printed)

- blue = closely related (say the same concept)

- pink = connected topics (may be excluded in smaller projects)

- green = summary (more general)

Most important outcome - increased understanding of your users, their behavious and needs. That can feed into personas, design ideas, low hanging fruits, strengths and weaknesses

Triangulation

Used to validate research results. Market research, surveys, usability testing & prototyping can confirm or refute the conclusions.

Make sure the data from contextual inquiry makes sense in terms of information from other sources.

Direct observation

The whole idea of doing an observational study is to really get that rich feeling of how people are behaving, interacting. Sometimes, you need to make the situation unnatural to find out what’s natural for people. Your report should be equally rich in the way it’s expressed.

The W questions

Why would you do direct observation?

- In interviews, people will give you their explicit knowledge (normative behavior)

- In observations, people will give you their tacit knowledge (normal behavior)

When you might do it?

- before you even start design to get context and see current processes

- at the ideation stage to check if it fits the culture of how stuff is done (technology probes)

- post-design to check does it actually work

Who and how many with?

- ideally real users, a small group of people

- relatively just a few users but in depth

- general lessons are coming out of your understanding, not out of data (“this is a behavior I expect from users”)

- normally, you and your buddy are the worst people to try things out

Potential audiences:

- Employees of a client - easy to get them, but must have inherent interest, not be forced

- Client’s clients. Avoid ex-clients of ex-client

- Target audience (surogatory users not ideal, but sometimes neccessary)

What they do?

- as natural as possible: with their own equipment, communcation

- a bigger commitment than a user test, but not that many clients

Where they do it?

- in users own environment, their space

- in a lab: similar to user study, but less control (with their own laptops)

difference is symbolic and practical - in their environment they feel more empowered and you - humble.

Managing trust

- be really open of what and how you collect and do with the info

- give them some control (allow to edit, redact)

- be clear of what are your connections to authority

- figure out what you are going to do in case of commercial sensitivity

During observation

Just like in sports, if you run, you don’t want to think about making steps. Observation is better as a fly on the wall than actively interacting.

You might like to make inverventions and disrupt the norm purposefully to get a chance to see what is happening or how they might interact with a technology probes.

What to observe:

- Behavior - what they do

- Words - what they say (especially to each other)

- Faces - what they feel, where they look

- Environment - where they are

- Artifacts - what is used (content, location, disposition)

You aim is to get to the point you feel them and are become an advocate of the user as you understand his point of view.

Analyzing results

You will always bring your own beliefs and biases to a research. What you can do is be aware of it and try to minimize the effect.

Estrangement

We are bad at noticing the obvious. To do it - make the normal strange!

- check out a comedian’s speech about the topic as they are really good at noticing small things and laughing about them

- analyst as a stranger (who does not know much about the topic) - note the strange things before they become normal

Appropriation

Using things in ways in which they are your use - work-arounds to get the job done.

If you don’t understand the workarounds, you can’t design for them.

Distance

Biggest challenge in observation is the huge amounts of data you get. So, you do as with all the other social studies - do a thematic analysis:

- identify key concepts, patterns and classes of behavior

- look for the “aha!” moments that have the potential to change your point of view

- don’t depend too much on theories and models as they narrow your vision

Dialectic (re)coding:

When you have summarized and made a model of the world, try to look at the outliers - what does not fit in?

There are two types of outliers:

- mind the gap: missing categories

just a: refining simplistic categories

[washing a car]

“It’s just leisure activity”

Is it really? Do you get the eerie feeling, tension? Try giving these a name.

Engagement

Another way is to DIY, enculturate yourself. But don’t forget yuo don’t know everything and take things back to the participants., referably after the experience is over.

Communicating results

The goal of user research is to get the team to the same level of understanding and empathy for the target audience as you do.

When you’re sharing results from qualitative user research efforts, you’re most likely focusing on creating an understanding for the lives people lead, the tasks that they need to fulfill, and the interactions they must effect so as to achieve what they need or want to do.

A list is not immersive enough to trigger any type of empathy.

Potential methods

Affinity diagram: group most influential post-its by main themes and present that.

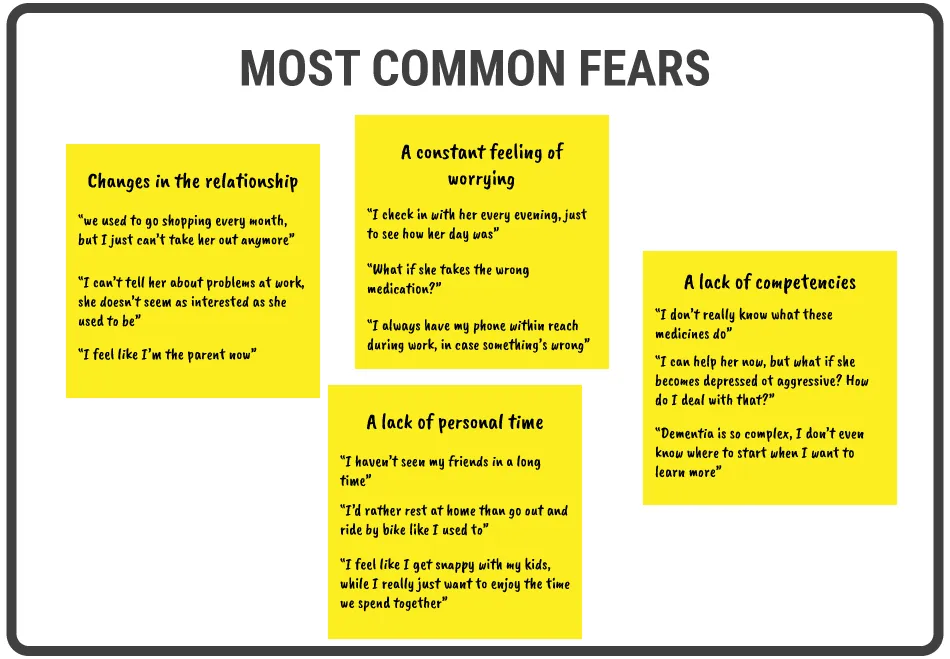

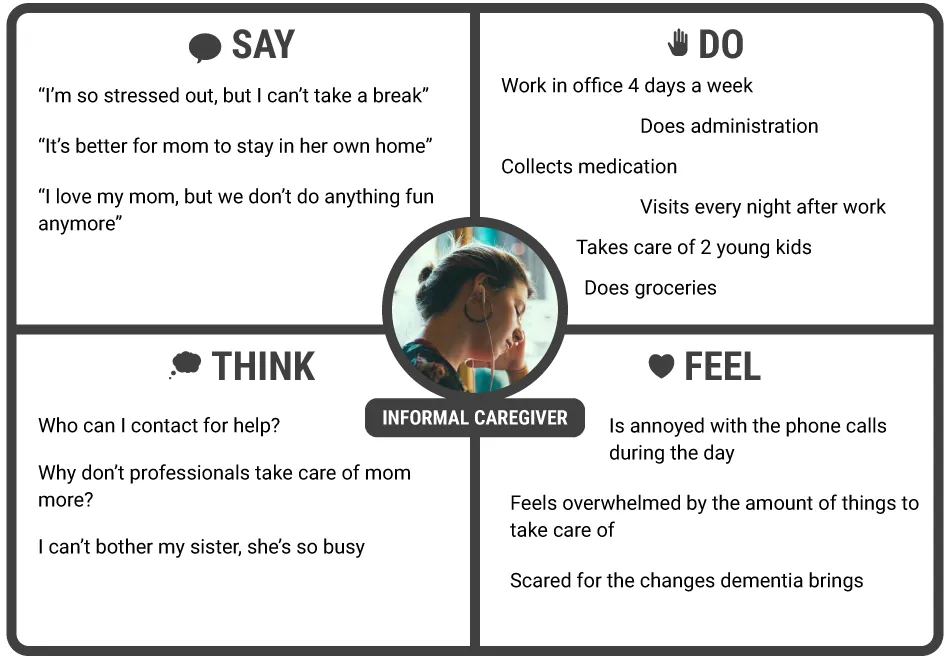

Empathy map: group post-its by “say, do think, feel”

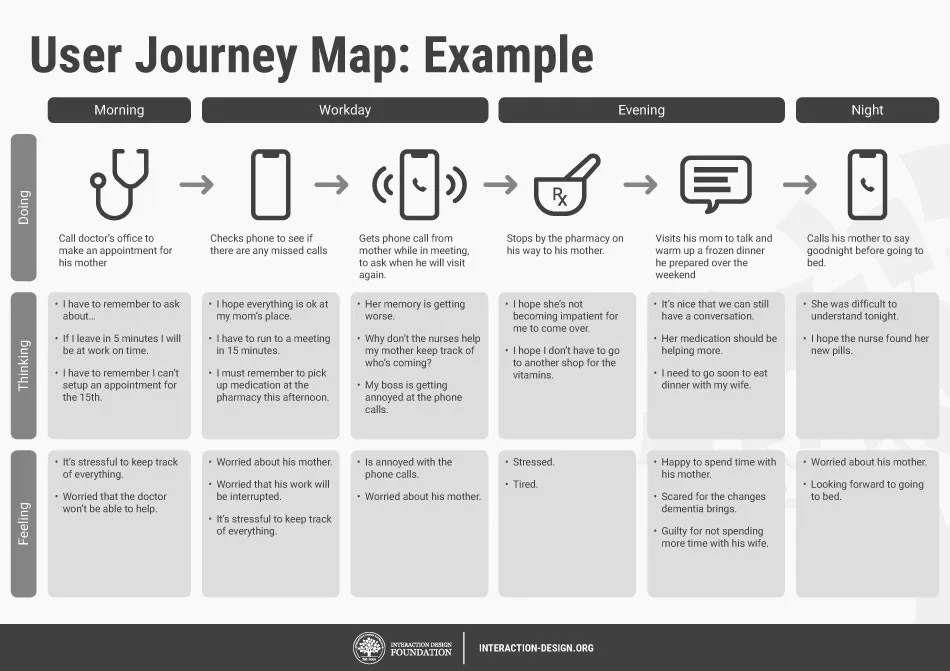

User Journey map: empathy map over a period of time

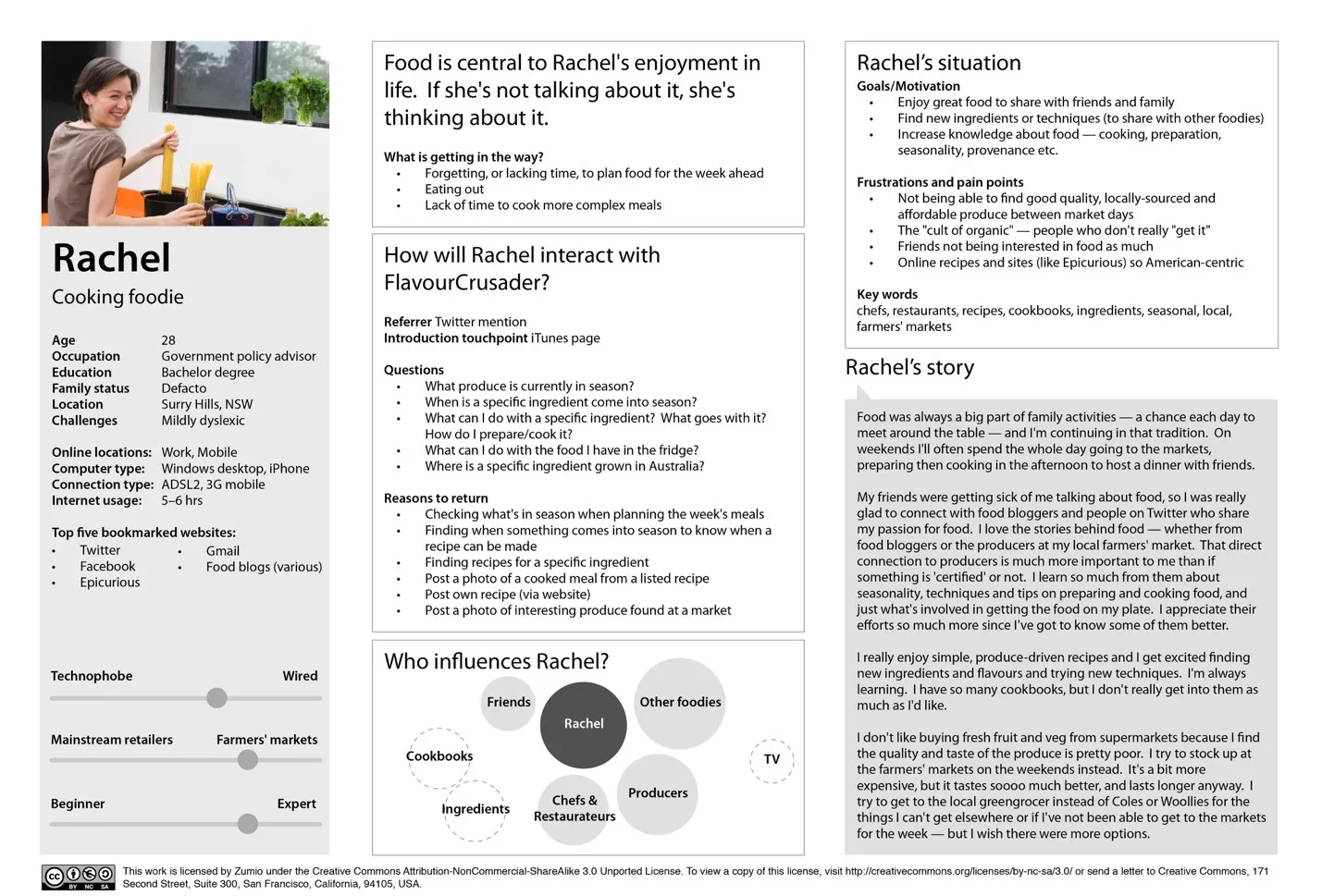

Personas

Personas

There are four perspectives that your personas can take to ensure that they add the most value to your design project:

- goal-directed personas

- role-based personas

- engaging personas

- fictional personas

There are six common pieces of information that make up a (fictional) persona:

- Name, age, gender, and an image of the persona, preferably including some context in the background

- A tag line, indicating what the persona does or considers relevant in his or her life

- The experience and relevant skills the persona has in the area of the product or service you will be developing

- Some context to indicate how he/she would interact with your product or service (e.g., the voluntariness of use, frequency of use, and preferred device)

- Any goals, attitudes, and concerns he/she would have when using your product or service

- Quotes or a brief scenario, that indicate the persona’s attitude toward the product or service you’re designing. If the persona already uses an existing product or service to meet his or her needs, you might describe the use of that here.

Without the research data, nobody in real life will use your designs; without fictional details, nobody in your design team will remember whom you’re designing for.

Further reading

Futher reading on coding about Grounded theory and check out a detailed discussion on challenges of coding and also a coding pyramid

Course materials (pdf)

Good questions for stakeholder interviews

Usability Test Metrics

Preparing for a Usability Test

Tips for Moderating Usability Tests

How To Ensure Rigor in Usability Tests

Advice for Writing Usability Test Reports

How to Structure a User Interview

Concrete Examples and Critical Incidents

How to Ask Open-Ended Questions

Semi-Structured Interviews – Different Types of Questions

Principles of Contextual Inquiry

Steps in a Contextual Inquiry Session

Tips and Tricks for Running a Contextual Inquiry Session

What to look out for when conducting observations

Practicalities and Difficulties of Conducting Observations

How to Carry out a Thematic Analysis - Steps in a Thematic Analysis

How to Carry out Follow-up Interviews

Examples

Usability Test Plan Example

Instructions to the Test Participant

Pre-Test Questionnaire

Post-Test Questionnaire

Usability Test Report

(Semi structured) Interview Guide